If a digital verification service (DVS) is user-facing, before it does something with a users’ identity or attribute information, the service must confirm that the user understands what is about to happen. CABs review how a service implements the rules for confirming user understanding from the trust framework as part of the certification process.

We’ve been asked what a ‘good’ confirmation that meets the requirements of the trust framework looks like.

What the rules say

The rules for confirming user understanding are found in sections 12.7.3. and 12.7.4. of the gamma (0.4) publication of the trust framework. A similar concept existed in the previous, beta version too – but we called it “user agreement” instead.

In broad terms, the rules require that a digital verification service:

- explains to a user what is happening to their data in “clear, plain language that is easy to understand”

- asks the user to positively confirm they understand

- explains what happens if they don’t agree

Services must also reconfirm the users’ understanding in certain circumstances.

It’s not the same as “consent”

Confirming user understanding is different from seeking “consent” under UK data protection law.

There may be similarities between what we call “confirming understanding” and what UK data protection law calls “consent”, but the trust framework does not require that “consent” is used as the legal basis for a service. Service providers can use any legal basis that is appropriate; it’ll depend on the service and what it’s for.

Instead, the rules in the trust framework regarding user confirmation are intended to give users as much understanding and control over how their data is used as possible. These rules are in addition to the transparency requirements under the UK GDPR.

Lengthy terms and conditions are not the answer

Services providers – not just digital verification ones – often have lengthy terms and conditions or “End User License Agreements” (EULAs). Users are often asked to accept these terms and policies before they use a service.

We don’t think that asking users to read and accept a complex policy statement is an effective way of confirming user understanding.

To get certified against the trust framework, services need to do more than that; they need be as simple as possible for users.

Lengthy, legalistic documents are not examples of clear, plain and easily understood language. There is plenty of evidence that they cannot reliably demonstrate that users positively agree to those terms.

The rules in the trust framework are intended to make using a digital verification service a genuine choice. Services shouldn’t rely on deceptive design patterns – like making it easier to accept than to decline a choice – to ‘nudge’ users towards accepting terms and conditions they may not fully be aware of or understand.

Use brief, straightforward prompts

When users install an app on a phone or computer, and open it for the first time, they are often asked for permission to access certain features, for example, to send notifications, to access location data, or to use the camera or microphone.

Different apps need different permissions at different times, so users are presented with different prompts. Permissions sometimes need to be refreshed, so the user sees the prompt at regular intervals. Often those prompts are customised by the developers of the apps to explain very briefly why they need those permissions, and a user can decide whether to permit the access.

The clarity of this model is what we’re trying to encourage for digital verification services. It puts what is happening front and centre for users. Services should provide:

- brief, straightforward prompts

- transparent explanations and clear choices, and

- an ability to find out more information if a user wants to understand what is happening in greater detail

Some examples

There are many ways that you could design an interface that confirms user understanding. As the trust framework is outcome-focused and technology-agnostic, we don’t mandate exactly what it should look like.

We would encourage service providers to try different approaches and to test their designs with real users through user research.

Here are some examples we came up with, inspired by things we’ve seen so far in real world services.

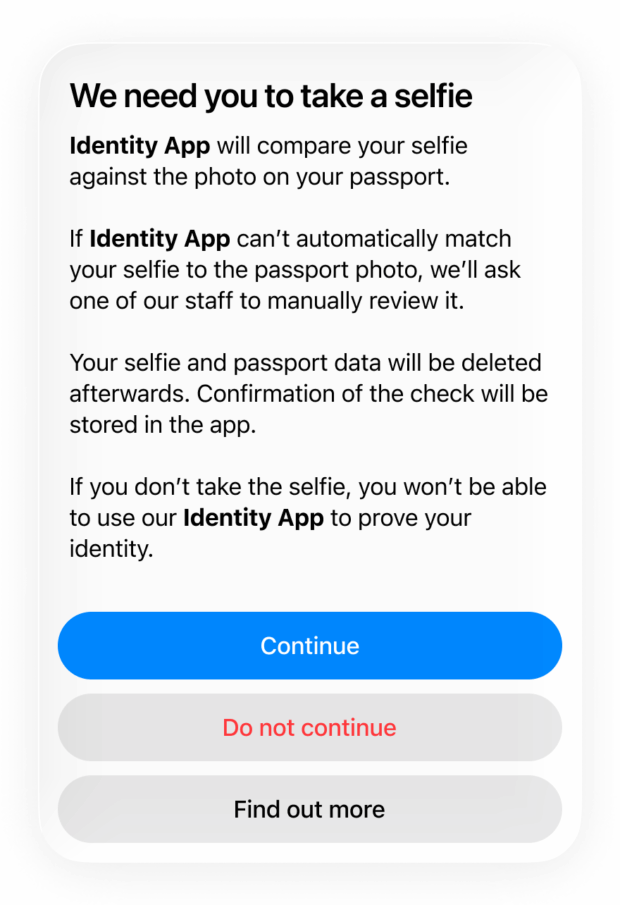

1. Asking permission to take a selfie

In this example, a user needs to take a selfie to match it to a passport photo they’ve already provided. They’re presented with a prompt before they take the selfie, so they can confirm their understanding.

This approach wouldn’t check off every part of the rules in sections 12.7.3, but it could meet some of them:

- the prompt explains what is about to happen in a way that is simple to understand

- the user is asked to confirm they want to continue before anything happens

- the user knows what will happen if they choose not to continue

The prompt itself should summarise everything that is happening with a user’s data. A “find out more” button is provided which could take the user to a more detailed explanation of what is happening; for example, it could link to a privacy notice. A service shouldn’t hide or introduce additional data processing behind that button.

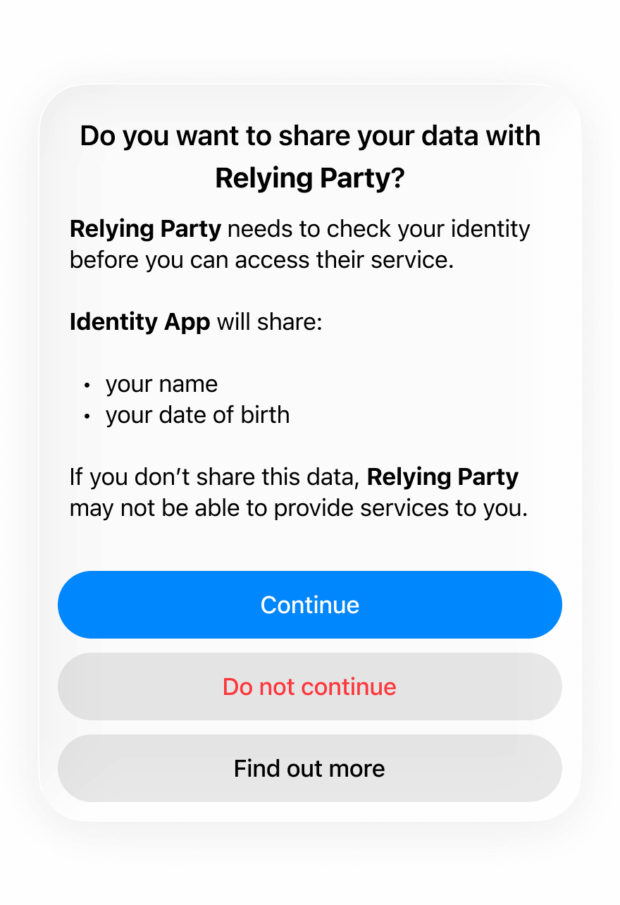

2. Sharing data with another service

In this example, a user already has an identity service set up and has been asked to share some attributes with an orchestration service acting on behalf of a relying party. It follows a similar pattern to the first example.

This example is one way you could attempt to comply rule with 12.7.4.c, which suggests that services could reconfirm a user’s understanding whenever there is a request to share or disclose data to a third-party.

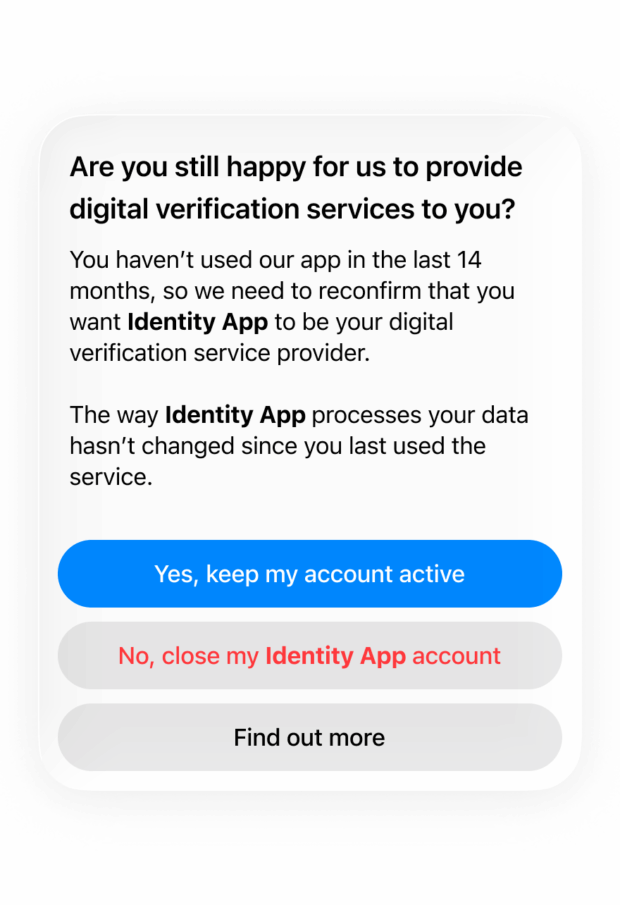

3. Reconfirm user understanding after a period of inactivity

Rule 12.7.4.b. requires that a service must reconfirm user understanding if more than 14 months have elapsed since a user last reconfirmed their understanding.

This example tries to explain, as plainly as possible, that the user needs to agree to keep their account active or, alternatively, can choose to close their account.

We want service providers to innovate

We should stress that these are only examples; they’re not whole solutions. Service providers don’t have to follow these examples in their services. These are just ideas that point in the right direction.

We want service providers to innovate and find great ways to achieve compliance with the rules.

We’d like to start to compile examples of best practice so we can share them with our approved conformity assessment bodies, to support consistent evaluations across the market. If you think your service confirms a users’ understanding well, we’d love to hear from you.